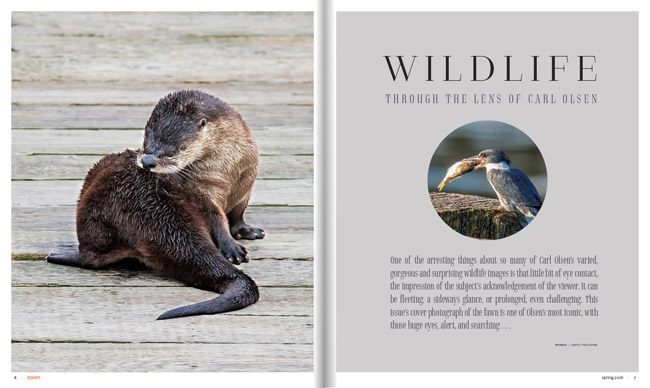

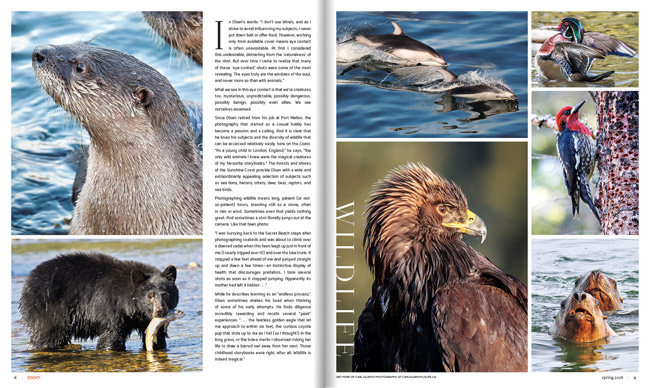

One of the arresting things about so many of Carl Olsen’s varied, gorgeous and surprising wildlife images is that little bit of eye contact, the impression of the subject’s acknowledgement of the viewer. It can be fleeting, a sideways glance, or prolonged, even challenging. This issue’s cover photograph of the fawn is one of Olsen’s most iconic, with those huge eyes, alert, and searching…

In Olsen’s words: “I don’t use blinds, and as I strive to avoid influencing my subjects, I never put down bait or offer food. However, working only from available cover means eye contact is often unavoidable. At first I considered this undesirable, detracting from the ‘naturalness’ of the shot. But over time I came to realize that many of these ʻ’eye-contact’ shots were some of the most revealing. The eyes truly are the windows of the soul, and never more so than with animals.” What we see in this eye contact is that we’re creatures too, mysterious, unpredictable, possibly dangerous, possibly benign, possibly even allies. We see ourselves assessed.

Since Olsen retired from his job at Port Mellon, the photography that started as a casual hobby has become a passion and a calling. And it is clear that he loves his subjects and the diversity of wildlife that can be accessed relatively easily here on the Coast. “As a young child in London, England,” he says, “the only wild animals I knew were the magical creatures of my favourite storybooks.” The forests and shores of the Sunshine Coast provide Olsen with a wide and extraordinarily appealing selection of subjects such as sea lions, herons, otters, deer, bear, raptors, and sea birds.

Photographing wildlife means long, patient (or not-so-patient) hours, standing still as a stone, often in rain or wind. Sometimes even that yields nothing great. And sometimes a shot literally jumps out at the camera. Like that fawn photo:

“I was hurrying back to the Secret Beach steps after photographing seabirds and was about to climb over a downed cedar when this fawn leapt up just in front of me (I nearly tripped over it!) and over the tree trunk. It stopped a few feet ahead of me and jumped straight up and down a few times—an instinctive display of health that discourages predators. I took several shots as soon as it stopped jumping. Apparently its mother had left it hidden…”

While he describes learning as an “endless process,“ Olsen sometimes shakes his head when thinking of some of his early attempts. He finds diligence incredibly rewarding and recalls several “peak” experiences: “…the fearless golden eagle that let me approach to within six feet, the curious coyote pup that stole up to me as I hid (so I thought!) in the long grass, or the brave merlin I observed risking her life to draw a barred owl away from her nest. Those childhood storybooks were right, after all. Wildlife is indeed magical.”

See more of Carl Olsen’s photography at carlolsenwildlife.ca.

Words | Nancy Pincombe