Spring can be cruel. Its relentlessness can mock those who feel tired, broken, or dispirited. We can feel left behind, overlooked by the creative force, depressed. Sometimes it takes a little help to move us back into the flow of life. Ceramic restoration artist Naoku Fukumaru understands these feelings very well. And she knows a little synchronicity can arrive just at the right time.

Born in Kyoto, Japan, into a third-generation antique auction house family, Fukumaru grew up surrounded by beautiful old things. An early interest in repairing the (inevitable) broken items in the family business put her on the path to a master’s degree in Conservation and Restoration from West Dean College in England. From there, she took on increasingly important roles doing restoration work all over the world. This has taken her to the USA, Europe, Japan, and Egypt for a long list of prestigious restoration assignments that in itself is a walk through art history: the Tomb of Tutankhamen in Egypt, Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper, The Thinker by Rodin, Caravaggio and Veronese paintings, murals by Diego Rivera. She has also worked on projects for such illustrious personages as Yoko Ono and sculptor Anish Kapoor.

Yet it was a move to Powell River, BC, four years ago, that redirected her life when it had taken a dangerous turn. At a very low point, Fukumaru was given a nudge by the universe in the form of a misdirected email asking about a workshop in the art of Kintsugi.

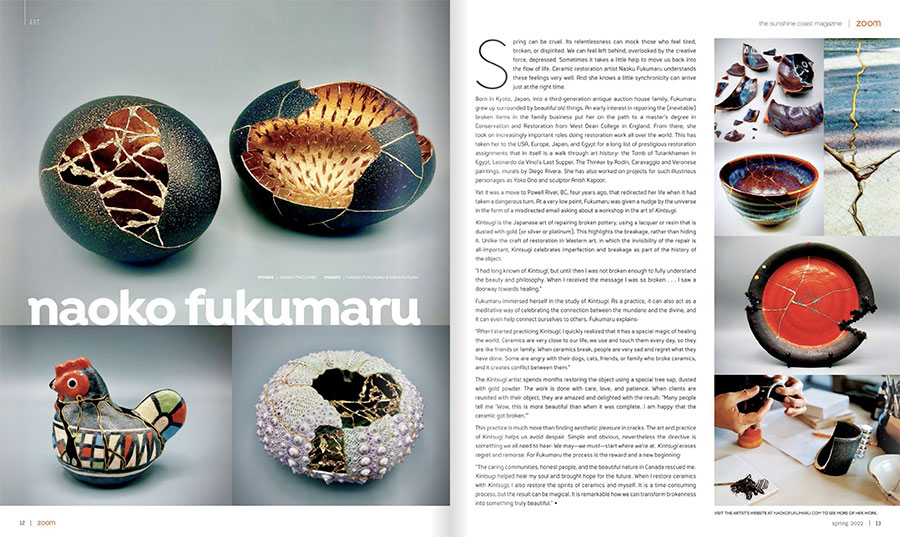

Kintsugi is the Japanese art of repairing broken pottery, using a lacquer or resin that is dusted with gold (or silver or platinum). This highlights the breakage, rather than hiding it. Unlike the craft of restoration in Western art, in which the invisibility of the repair is all-important, Kintsugi celebrates imperfection and breakage as part of the history of the object.

“I had long known of Kintsugi, but until then I was not broken enough to fully understand the beauty and philosophy. When I received the message I was so broken . . . I saw a doorway towards healing.”

Fukumaru immersed herself in the study of Kintsugi. As a practice, it can also act as a meditative way of celebrating the connection between the mundane and the divine, and it can even help connect ourselves to others. Fukumaru explains:

“After I started practicing Kintsugi, I quickly realized that it has a special magic of healing the world. Ceramics are very close to our life; we use and touch them every day, so they are like friends or family. When ceramics break, people are very sad and regret what they have done. Some are angry with their dogs, cats, friends, or family who broke ceramics, and it creates conflict between them.”

The Kintsugi artist spends months restoring the object using a special tree sap, dusted with gold powder. The work is done with care, love, and patience. When clients are reunited with their object, they are amazed and delighted with the result: “Many people tell me ‘Wow, this is more beautiful than when it was complete. I am happy that the ceramic got broken.’”

This practice is much more than finding aesthetic pleasure in cracks. The art and practice of Kintsugi helps us avoid despair. Simple and obvious, nevertheless the directive is something we all need to hear: We may—we must—start where we’re at. Kintsugi erases regret and remorse. For Fukumaru the process is the reward and a new beginning:

“The caring communities, honest people, and the beautiful nature in Canada rescued me. Kintsugi helped heal my soul and brought hope for the future. When I restore ceramics with Kintsugi, I also restore the spirits of ceramics and myself. It is a time-consuming process, but the result can be magical. It is remarkable how we can transform brokenness into something truly beautiful.”